Lob der Charge

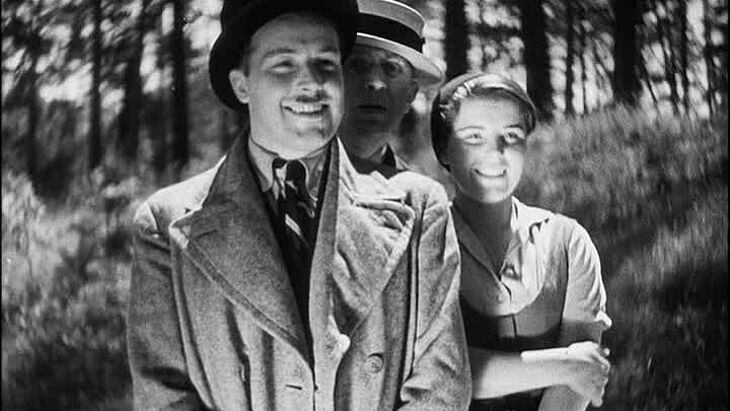

The wonderful supporting actors of early German sound comedy (1930-1933)

"The acting characters in our films break down (...) at first glance into two parts. Into the heroic players and the chargen players." In 1931, Berlin film critic Rudolf Arnheim was referring to the numerous sound film comedies with stars such as Willy Fritsch and Lilian Harvey, Gustav Fröhlich, Renate Müller and Käthe von Nagy. Arnheim finds the dazzling-looking and immaculately coiffed stars, who always appear cheerful, youthful and vital as heroes, completely interchangeable. In his view, they are purged of everything that actually constitutes a personality.

Quite different are the actors in smaller or larger supporting roles: They are the ones who provide flavor, wit and spice; they bring individuality and reality to stories that are often knitted to a similar pattern. "The charge player shows people as they are, the hero player shows them as one would like them to be." The title of Arnheim's article, which appeared in the trade journal Filmtechnik in October 1931, is then programmatically called: Praise of the Charge.

In theater and film, a minor character with exaggerated qualities is called a charge. Their role is often typified, lives mostly from physicality and aims at comic, even grotesque effect. Charges are fat or thin, phlegmatic or hyperactive, they are almost mute or talk like a waterfall. Chargen are many things at the same time: a type and its individual interpretation; a cliché and its subversion; an expectation that is played with.

In the best cases, the chargen act virtuously, obstinately, surprisingly. And the early sound film era offers them opportunities for this. The actors, many of whom had been socialized at stages, cabarets and revue theaters in the turbulent Berlin of the 1920s, and who now appear in the film in chargen roles, become audience favorites. Siegfried Arno and Felix Bressart even get leading roles in which they take their foibles and antics to extremes. They are always unmistakable - and never as silly as they might look: whether the thundering despot Adele Sandrock or the bubbling Otto Wallburg, the ever-contradictory linguistic artist Szöke Szakall or the chansonnière Lotte Werkmeister, whether Julius Falkenstein, whom nothing shakes, or Kurt Gerron, who floats like a ballerina despite a giant belly. Or the authoritarian Senta Söneland in a duel with the rotundly witty Karl Huszár-Puffy.

Many of these actors were Jews. Their careers in German film came to an abrupt end with the onset of the National Socialist dictatorship and the state-imposed ban on working. Like the critic Rudolf Arnheim, they were expelled and persecuted. The public favorites Kurt Gerron, Otto Wallburg and Kurt Lilien died in German extermination camps. They all contributed to the fact that in the sound film comedies for a time the hierarchies begin to dance: What is important and shines brightly sometimes turns, at least in the view of the audience. From the periphery, the batches make their way to the center.

With special thanks to Guido Altendorf, Rolf Aurich, Martin Erlenmaier, Florian Höhensteiger and Fabian Schmidt.