How National Socialist artists continued their careers after 1945

“Divinely Gifted”. National Socialism’s favoured artists in the Federal Republic (27 August to 5 December 2021)

Download

Many renowned protagonists of the National Socialist art scene continued working in the Federal Republic as full-time visual artists after 1945. They produced works to be displayed in public spaces, received lucrative commissions from government, industry and church organisations, taught at art academies, submitted proposals to art competitions and were represented in exhibitions. Their designs for statues, reliefs and tapestries on public squares and façades or in theatre and cinema foyers have left their mark to this day on the face of many city centres. They were able to profit from the anti-modernist climate in the early post-war decades.

In an exhibition opening on 27 August 2021, the Deutsches Historisches Museum takes the “Divinely Gifted List” as the point of departure for a study of the largely neglected topic of the post-war careers of such “divinely gifted” artists as Arno Breker, Hermann Kaspar, Willy Meller, Paul Mathias Padua, Werner Peiner, Richard Scheibe and Adolf Wamper. The list was first compiled on behalf of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels in August 1944: 378 artists, among them 114 sculptors and painters, were considered “indispensable” and were exempted from military duty and work assignments.

The exhibition “‘Divinely Gifted’. National Socialism’s favoured artists in the Federal Republic” (27 August – 5 December 2021) shows for the first time the strong presence of these artists in public spaces, but also in the institutions of political, economic and cultural life in post-war Germany. It also examines their networks, the choice of their motifs, and the reception of their works as well as the related questions of continuity and adaptation to the new circumstances. Reinforced by the parallel exhibition “documenta. Politics and Art” (18.6.2021 – 9.1.2022), the idea of a supposedly radical, cultural-political new beginning in the young Federal Republic has thus had to be revised.

Prof. Dr Raphael Gross, President of the Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum: “The popularity of the ‘divinely gifted’ artists and their visual contribution to Nazi ideology were immense. At first glance, their involvement in the antisemitic and anti-modernistic Nazi art scene would seem to preclude an unbroken continuation of their careers after 1945. The finding of our exhibition is therefore all the more surprising: numerous traces of their work can still be found in the public space. The examination of this legacy remains a challenging task.”

Sculptures, paintings, tapestries, models, drawings, photographs, film and sound documents, posters, original publications as well as TV and press reports on two floors of the museum demonstrate how the former “divinely gifted” painters and sculptors were able to continue, into the 1970s, their full-time work as artists in the Federal Republic and in Austria, but also in individual cases in the GDR, outside of the realm of the major museums. Exemplary biographies and networks in different cities demonstrate the structural latitude that allowed these artists to continue their careers. Taking the example of such works as Arno Breker’s “Pallas Athena” (1957), curator Wolfgang Brauneis points out the stylistic and iconographic peculiarities and the circumstances of their origin, and examines their reception. With the sculpture in Wuppertal, Arno Breker temporarily took leave of the monumentality of the sculptures that can still be seen at the former Reichssportplatz at the Olympiapark in Berlin. Pallas Athena had also been a popular motif in the Nazi period. Breker received the commission through the intercession of the fellow “divinely gifted” architect Friedrich Hetzelt.

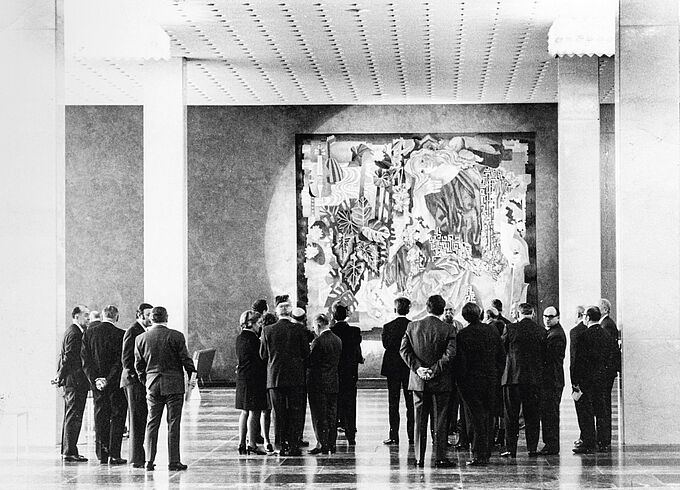

In order to satisfy the expectations of the public commissioners and the taste of a wider audience, the artists sometimes conformed the content and style of their works to the respective political system. Unlike the case of the works of Modern Art, there were hardly any debates or protests against the presentation of representational works by the formerly renowned artists of National Socialism. An exception was Hermann Kaspar’s tapestry “Lady Musica” (1969) in the Nuremberg Meistersingerhalle. This gift of the state of Bavaria to the city of Nuremberg led to year-long discussions. By contrast, highly symbolic memorials such as Richard Scheibe’s “Memorial for the Victims of 20 July 1944” (1953) in the Berlin Bendlerblock or Willy Meller’s sculpture “The Mourning Woman” (1962) in front of the first Federal German National Socialist documentation centre in Oberhausen evoked almost no critical response. Richard Eichler’s anti-modernist bestseller “Könner, Künstler, Scharlatane” (1960) demonstrates that neither the artists nor the National Socialist concept of art had disappeared after 1945.

When Federal President Theodor Heuss opened the first documenta in 1955, the visual artists of National Socialism could not be represented there because their careers and works were not compatible with the self-understanding propagated by the young Federal Republic. However, numerous representative commissioned works showed that these artists were in fact closely tied to the cultural-political programme of the Federal Republic. Only two months before the first documenta, Heuss had opened the Congress Hall of the German Museum in Munich. Hermann Kaspar, chief furnisher of the New Reich Chancellery, had begun work on hall’s monumental wall mosaic in 1935 and then completed it, after wartime interruptions, in 1955.

In its geographical quest for traces, the DHM’s historical-critical exhibition leads back up to the present day: a multimedia presentation at the end of the exhibition documents around 300 works by artists from the “Divinely Gifted List” that were made during the National Socialist period or after 1945 and are still on display in the public space in Germany and Austria.

The exhibition is supported by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes.

Press images in high resolution acan be downloaded after registering or loggin in.

Unveiling of Hermann Kaspar’s Lady Musica in the Meistersingerhalle in Nuremberg, 12 January 1970 © Stadtarchiv Nürnberg, E 55 Nr. 176

12 January 1970 © Stadtarchiv Nuremberg, E 55 Nr. 176